ENSO

ENSO Outlook: May 2024

This page considers the ENSO outlook for the next three to six months, and the typical impact of El Niño and La Niña events on rainfall in Southeast Asia.

Current SST conditions are shown on the climate monitoring node website: sst - SEA Climate Monitoring

Latest Climate Outlook (December 2023 – May 2024): El Niño likely to continue during DJF 2023/2024, with global climate models predict the El Niño conditions to gradually weaken, though continue to indicate El Niño conditions for much of the first half of 2024

Updated: Dec 2023

Recent analysis of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies over the equatorial Pacific shows well above-average SSTs over the Nino3.4 region, along with atmospheric indicators such as trade wind strength and cloudiness, indicating El Niño conditions.

For DJF 2023/2024, the current El Niño conditions are likely to continue. After DJF 2023/2024, global climate models predict the El Niño conditions to gradually weaken, though continue to indicate El Niño conditions for much of the first half of 2024. The peak strength of the ongoing El Niño, based on Nino3.4 index, is predicted to be moderate to strong.

The full ASEANCOF-21 Outlook Bulletin (DJF 2023/2024) can be found in the Consensus Bulletin for June-July-August (JJA) 2023 Season document.

Latest Model Outlook

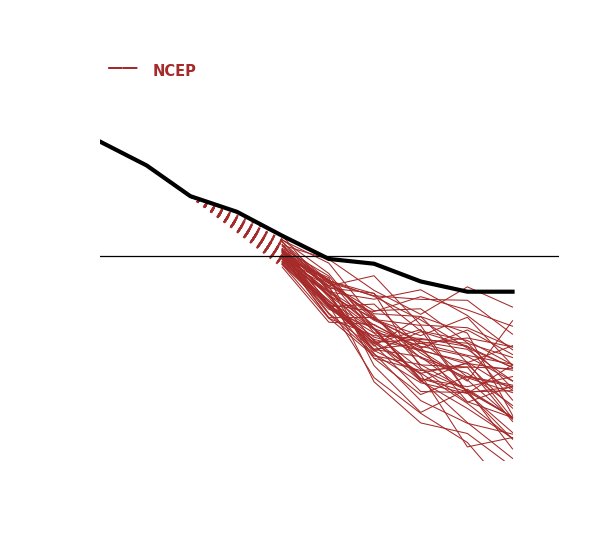

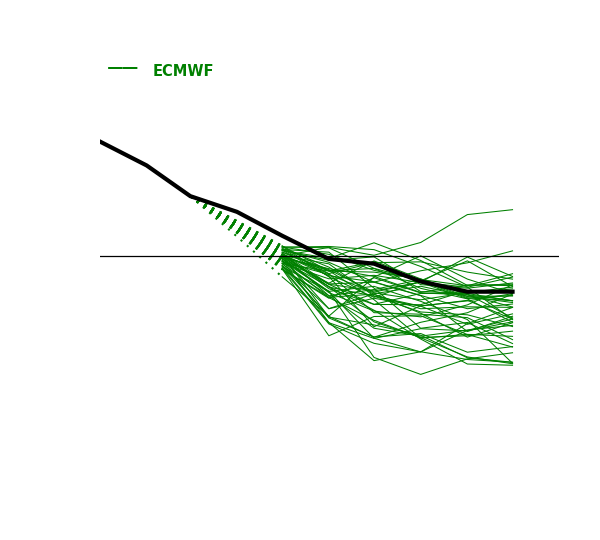

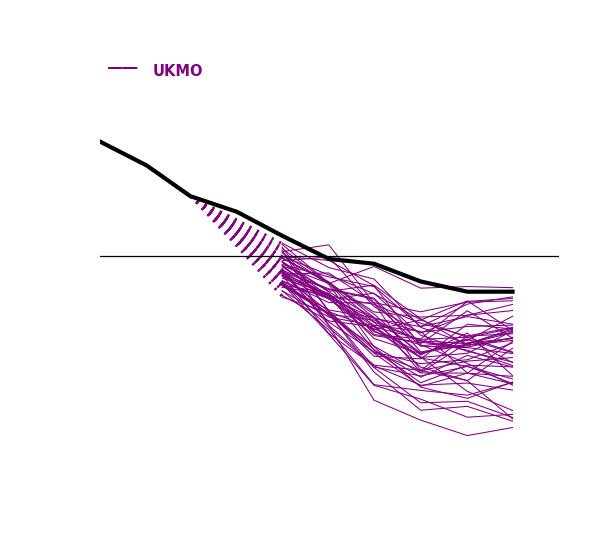

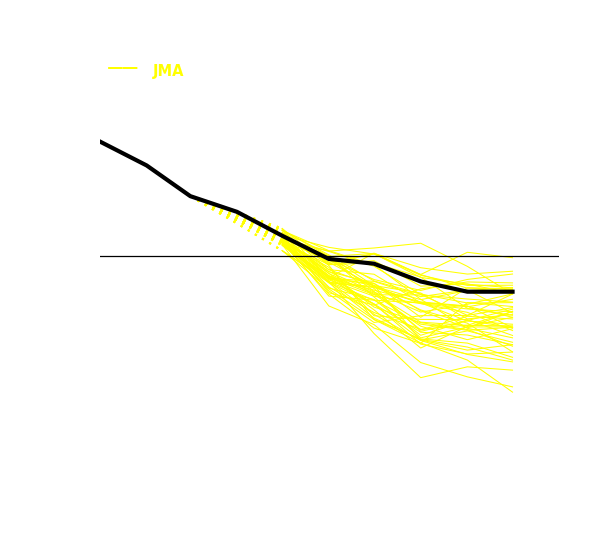

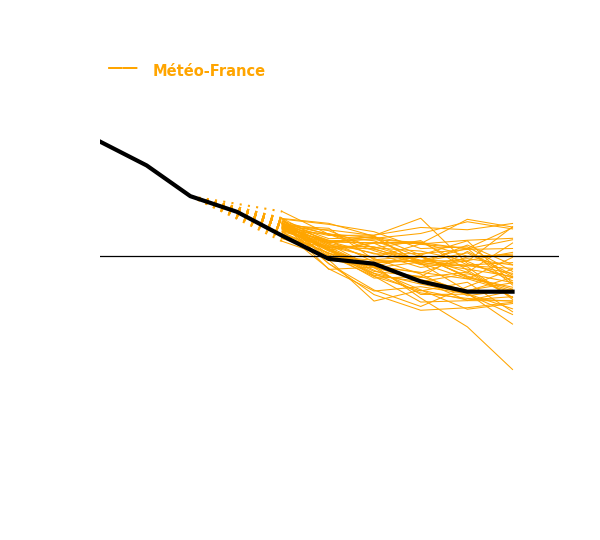

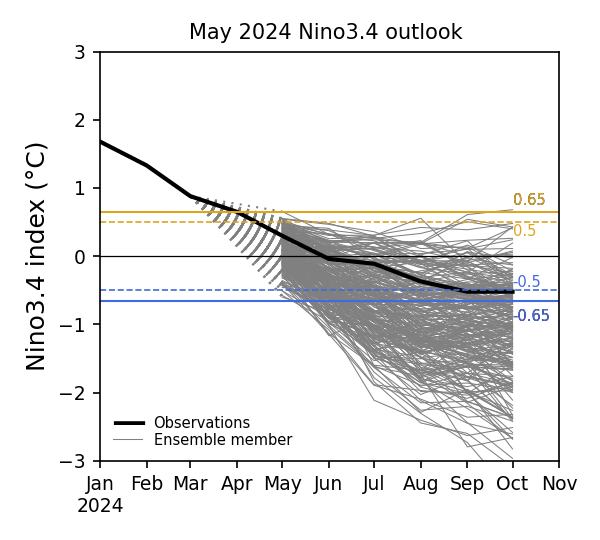

Model outlooks from Copernicus C3S (Figure 1), based on the Nino3.4 SST index, show that most models predict ENSO-neutral conditions during June and July 2024. While some models are indicating potential La Niña conditions from June onwards, there is considerable uncertainty in the long-term forecasts at this time of the year. However, it is unlikely that El Niño conditions will re-develop during this time.

Impact of El Niño/La Niña on Southeast Asia

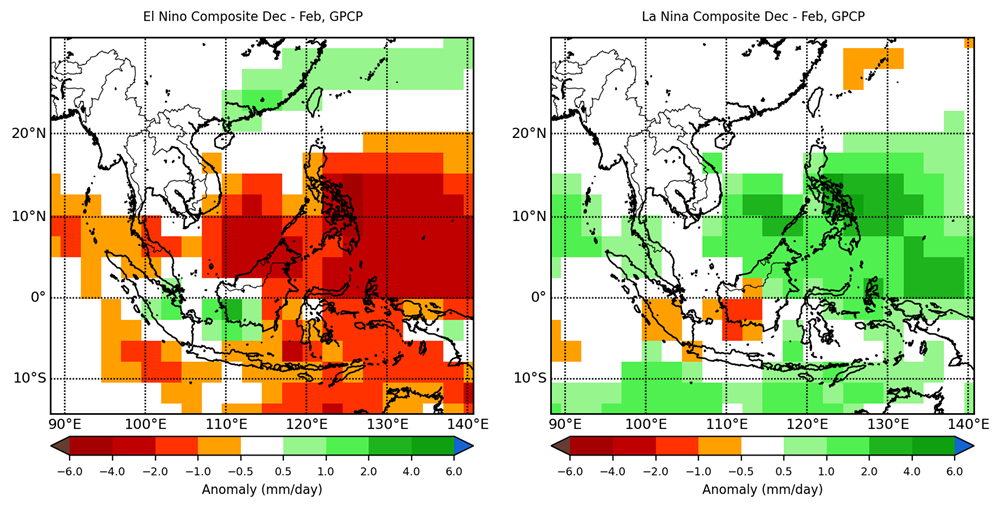

The typical impact of El Niño on Southeast Asia is drier-than-average rainfall conditions, including for much of the Maritime Continent during December to February (Figure 2, left). Warmer temperature conditions typically follow drier periods.

The opposite conditions for rainfall (and consequently temperature) are observed during La Niña years (Figure 2, right).

The impact on the region’s rainfall and temperature from ENSO events is more significantly felt during strong

or moderate-intensity events. Also, no two El Niño events or two La Niña events are exactly alike in terms of their impact on the region.

Figure 2: December to February (DJF) season rainfall anomaly composites (mm/day) for El Niño (left) and La Niña (right) years. Brown (green) shades show regions of drier (wetter) conditions. Note that this anomaly composite was generated using a limited number of El Niño and La Niña occurrences between 1979 and 2021 and therefore should be interpreted with caution (data: The Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Analysis Version 2.3).

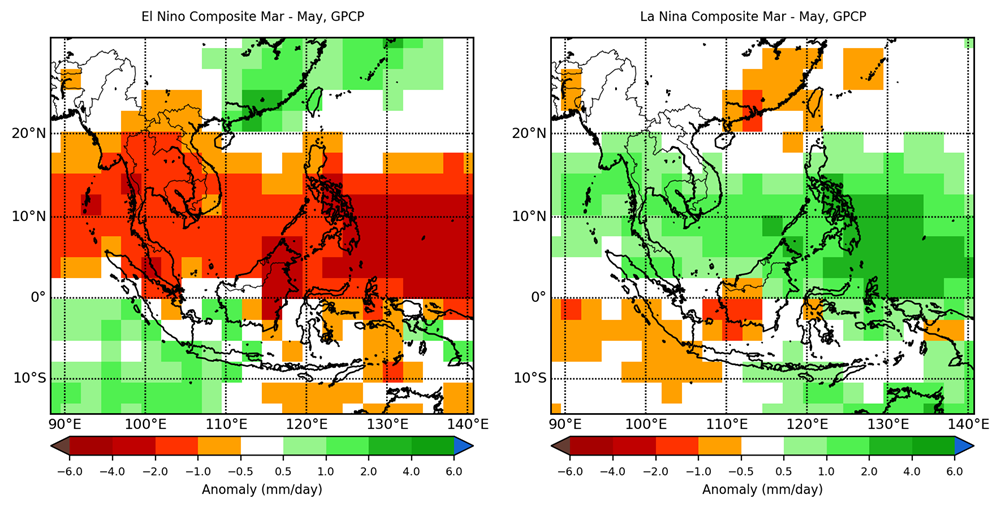

The typical impact of El Niño on Southeast Asia is drier-than-average rainfall conditions, including during March to May (Figure 2, left). Warmer temperature conditions typically follow drier periods. The opposite conditions for rainfall (and consequently

temperature) are observed during La Niña years (Figure 2, right).

The impact on the region’s rainfall and temperature from ENSO events is more significantly felt during strong or moderate-intensity events. Also, no two El Niño

events or two La Niña events are exactly alike in terms of their impact on the region.

Figure 2: March to May (MAM) season rainfall anomaly composites (mm/day) for El Niño (left) and La Niña (right) years. Brown (green) shades show regions of drier (wetter) conditions. Note that this anomaly composite was generated using a limited number of El Niño and La Niña occurrences between 1979 and 2021 and therefore should be interpreted with caution (data: The Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Analysis Version 2.3).

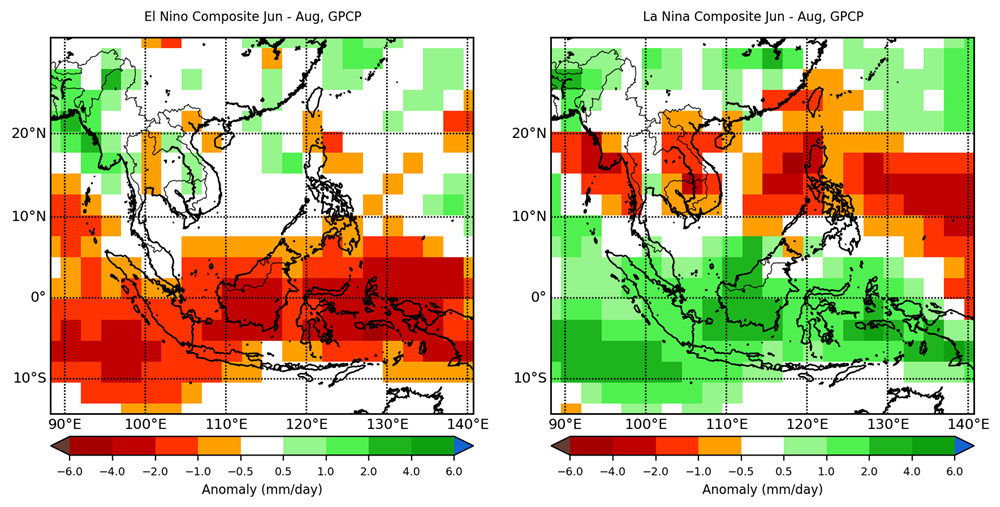

The typical impact of El Niño on Southeast Asia is drier-than-average rainfall conditions, including for much of the Maritime Continent during June to August (Figure 2, left). Warmer temperature conditions typically follow drier periods. The opposite

conditions for rainfall (and consequently temperature) are observed during La Niña years (Figure 2, right).

The impact on the region’s rainfall and temperature from ENSO events is more significantly felt during strong or moderate-intensity events. Also, no two El Niño events or two La Niña events are exactly alike in terms of their

impact on the region.

Figure 2: June to August (JJA) season rainfall anomaly composites (mm/day) for El Niño (left) and La Niña (right) years. Brown (green) shades show regions of drier (wetter) conditions. Note that this anomaly composite was generated using a limited number of El Niño and La Niña occurrences between 1979 and 2021 and therefore should be interpreted with caution (data: The Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Analysis Version 2.3).

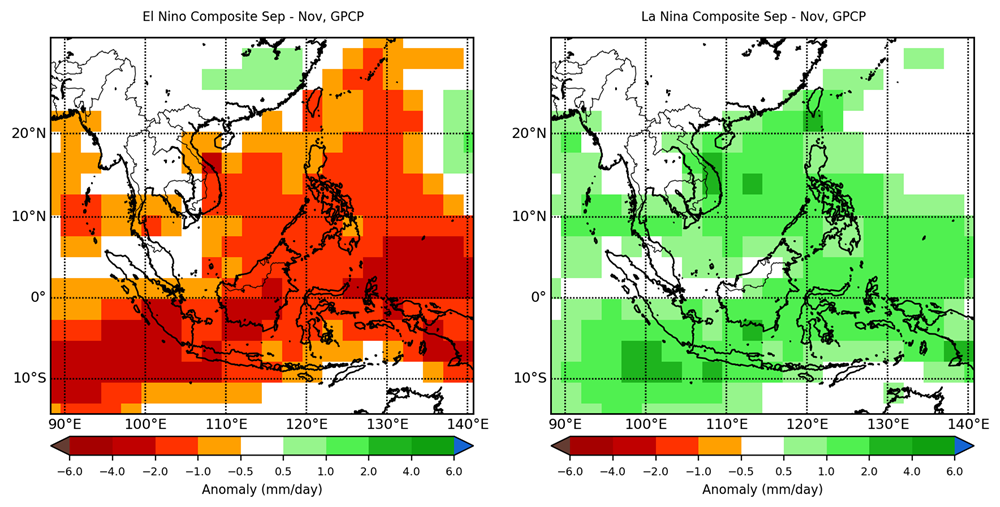

The typical impact of El Niño on Southeast Asia is drier-than-average rainfall conditions, including for much of the Maritime Continent during September to November (Figure 2, left). Warmer temperature conditions typically follow drier periods.

The opposite conditions for rainfall (and consequently temperature) are observed during La Niña years (Figure 2, right).

The impact on the region’s rainfall and temperature from ENSO events is more significantly felt during strong or moderate-intensity events. Also, no two El Niño events or two La Niña events are exactly alike in terms of their

impact on the region.

Figure 2: September to November (SON) season rainfall anomaly composites (mm/day) for El Niño (left) and La Niña (right) years. Brown (green) shades show regions of drier (wetter) conditions. Note that this anomaly composite was generated using a limited number of El Niño and La Niña occurrences between 1979 and 2021 and therefore should be interpreted with caution (data: The Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Analysis Version 2.3).